PDF document available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/PB147.pdf

Old age disadvantage begins at birth

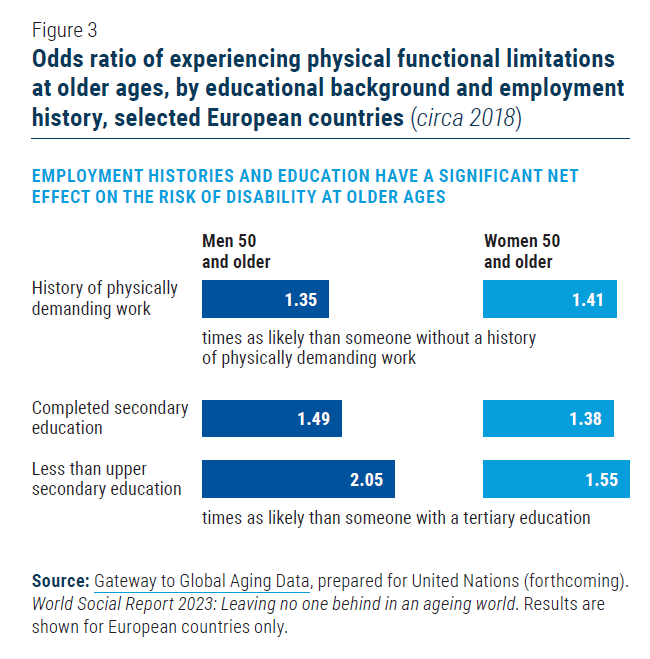

Much of the inequality between older persons has its roots in early life conditions. Without policies to prevent it, disadvantages reinforce one another through peoples’ lives, leading to large disparities among older adults. A life course perspective on ageing is critical to improving people’s health and well-being throughout the life course into old age.

Disability as a marker of inequality at older ages

The onset and severity of disability – affecting either physical or mental health – profoundly impacts the lives of people and their families and incurs large economic and societal costs in terms of health care and caregiving needs.

Disability is a key outcome of unequal ageing as it has been tied to both early life conditions, such as childhood poverty and later life risk factors, including health behaviors, occupation and chronic stress. Examining physical functional limitations as a measure of disability lends itself to cross-national comparisons of inequalities in health in old age as it measures difficulties that people face in carrying out tasks in their daily living, and does not depend on access to health care and medical professionals for diagnosis, as is the case for examining differences in the prevalence of diseases, such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Education is a key determinant of disability onset at older ages

Education consistently emerges as a primary determinant of health and economic outcomes throughout a person’s life, including at older ages. This holds true in the case of disability as well.

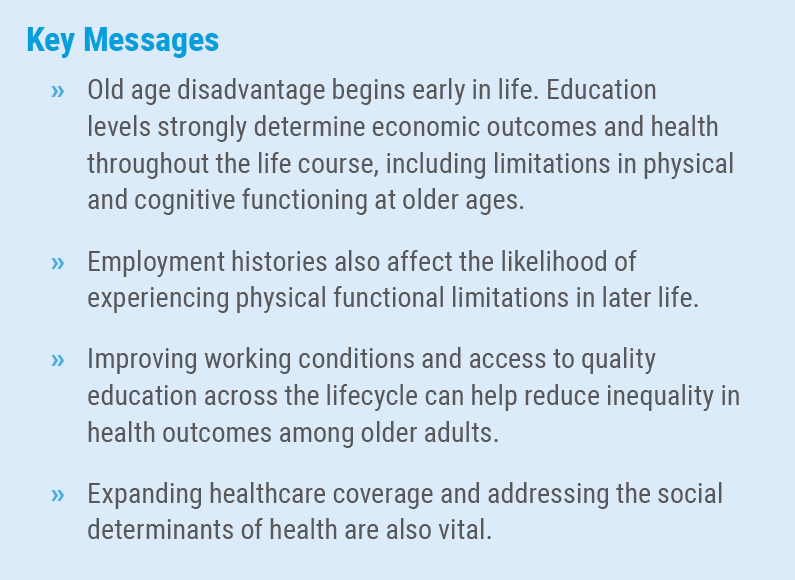

There is a significant difference in the experience of physical functional disability between the least and most educated adults 50 and older across countries. On average, the prevalence of disability is twice as high among older adults with low levels of education than the highly educated (figure 1). In some developed countries, levels of disability among the less educated are as high as in the developing countries shown. The disability gap differs by country owing, in part, to differences in social protection coverage, levels of spending on public education and support to workers and families with children (see, for example, Leopold, 2018).

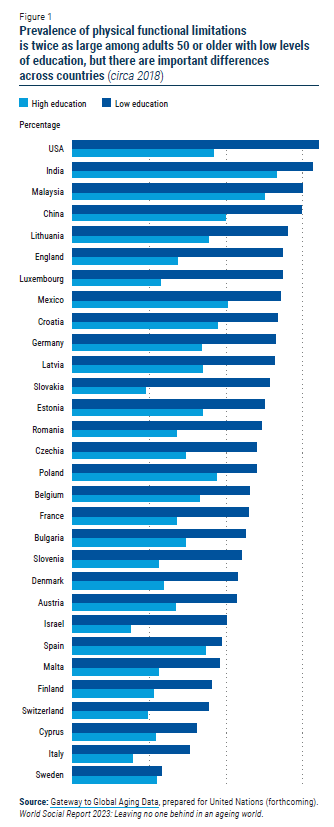

As with other health outcomes, a person’s own education holds strong predictive power for the experience of disability in later life. Yet in some cases, parental education also influences the likelihood of experiencing disability at later ages. Figure 2 illustrates the relative odds that someone will experience functional limitations at older ages. A number larger than one indicates a higher likelihood of experiencing disability than those in the reference group. In this figure, those with a lower education – or whose parents had a lower education – are more likely to experience functional limitations at ages 50 or older than those people who themselves or their parents completed tertiary education.

The data shows that lower levels of parental education reflect economic and social hardships early in life, although to a lesser degree than people’s own level of education (figure 2). Experiencing material hardship, such as living in poverty and nutritional deficiencies, in utero and in early life contributes, for example, to the risk of developing chronic conditions, poor adult cognition and greater sensitivity to stress (Ferraro and Shipee, 2009). Since a parent’s education is an important determinant of household wellbeing, it affects the social and economic conditions experienced in childhood. These findings suggest that more challenging social and economic conditions in childhood (as measured by parent’s education) can have a lasting impact on later life health, while one’s own educational achievements slightly moderate their effects.

Physically demanding jobs take a physical toll

While critical, early life circumstances are not the only determinant of health in old age – employment histories during adulthood also play a role. The relationship between health and employment can go both ways: poor health can negatively affect employment opportunities, while people’s type of work, the conditions in which they work and whether they have a job impacts their physical and mental health.

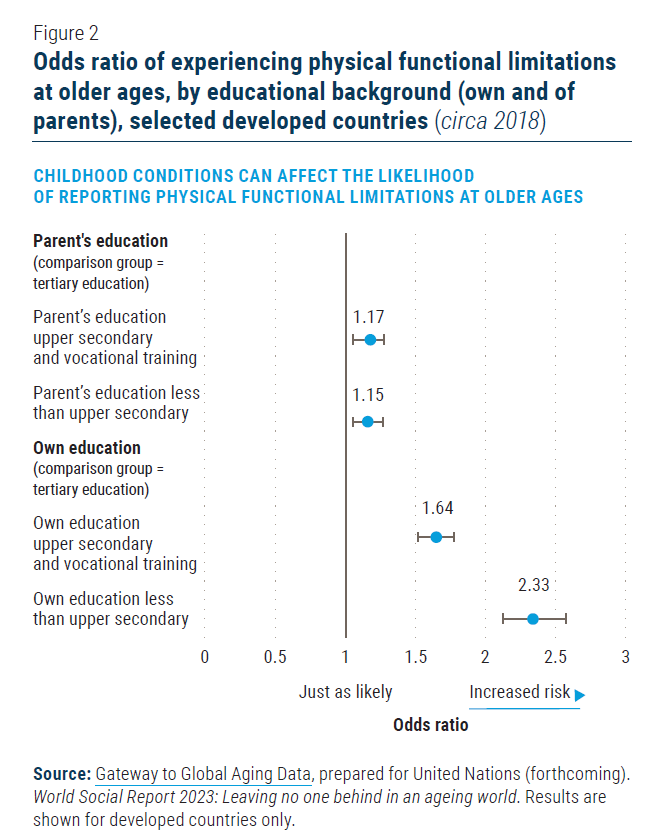

The physical demands of a person’s job history directly affect disability in their late working lives, regardless of their education. In European countries, men and women who held mainly physically demanding jobs since they started working were at 35 and 41 per cent greater risk of disability by the age of 50, respectively, than those who did not (see figure 3). For women, the effect of having worked in physically demanding jobs on the experience of disability is as large as the effect of not having a higher education.

The significant effects of both employment characteristics and education on physical functional disability at older ages suggest distinct pathways linking each to healthy ageing. Job demands may increase the risk of injury or other health risks that can lead to disability and poor health in old age, while education likely affects health behaviours. Low educational attainment may also reflect other characteristics of a person’s work history that have negative effects on health, such as episodes of unemployment, precarity and low wages.

Policy directions

In 2020, the World Health Organization and United Nations designated 2021-2030 as the Decade of Healthy Ageing. Its purpose is to promote strategies, grounded in solid evidence, that support well-being among older people. It advocates developing and maintaining functional abilities that depend on the intrinsic capacity of each individual, the surrounding environment and the interaction between the two.

Ensuring healthy ageing should be a key priority as countries grow older. Maintaining good physical and mental health over the life course is important in itself and helps to prevent falls into poverty, promoting the income security of older persons. Addressing disadvantage and inequality in health outcomes is important both for people today, but also in the future as negative health outcomes compound over time. Evidence on the life course factors determining health at older ages points to three areas for policy action that could improve health and well-being for all and lessen health disparities among older adults.

Universal social protection coverage, including universal access to health care services. The World Health Organization’s life course approach to health emphasizes the need to give children a healthy start and prevent illness at all ages. Without health insurance, many people become seriously ill or fall into poverty due to an inability to afford the cost of health care. Accelerating universal health coverage will reduce the amount of out-of-pocket spending on health, thereby protecting vulnerable groups from financial hardship while improving access to health services. Several developing countries have shown that it is feasible at various levels of development to extend access to a minimum standard of health care to the entire population. Moreover, several countries have been able to narrow the ethnic gap in health insurance through national, tax-financed schemes (United Nations, 2018), an important step to closing health gaps between different ethnic groups where they exist.

The higher likelihood of people with lower education and physically demanding jobs to experience functional disability at older working ages (50 years old or older) suggests that many people will not be able to remain in the labour force until retirement age, or will be forced to keep working despite their health problems. Policies can ensure economic security for those for whom retirement is a necessity but not a financial reality through social protection systems. Brazil, for instance, has employed a mix of tax-financed and contributory disability benefits that has enabled the country to achieve universal social protection coverage of persons with disabilities (United Nations, 2018).

Delinking social status and disability by promoting healthy behaviours. The effects of a person’s education and employment on the likelihood of experiencing disability in later life are partly due to differences in health behaviours and exposure to health risks according to social status. Obesity, smoking, alcohol use, a lack of exercise and exposure to environmental and occupational hazards take their toll on people’s health, and are more common among those with lower education levels. These health behaviours can increase the risk of accidents and non-communicable diseases such as cancer, heart disease and diabetes, which are also precursors to developing disability. Low-cost health screenings, expanded access to preventative care, and better health education can help break the relationship between social status and the onset and severity of disability at older ages.

Ensuring universal access to education to promote well-being throughout the life course. Giving every person an equal chance to grow older in good health and with economic security begins with promoting equal access to opportunities from birth. In particular, a person’s education, and sometimes even that of their parents, influences their incomes, access to health care, lifestyles, health behaviours and social networks. The significant education gradient in health and well-being across the life course argues for improving access to quality education for all, not only as a stand-alone goal but also as part of health policy.

Author: Maren Jiménez, Global Dialogue for Social Development Branch, Division for Inclusive Social Development, UN DESA. Note: This Policy Brief draws on work undertaken for the forthcoming World Social Report 2023: Leaving no one behind in an ageing world. Data and analysis presented here comes from the Gateway to Global Aging team based at the University for Southern California.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations