The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures needed to contain its spread have had a devastating impact on the world of work. According to ILO’s latest estimates, the crisis resulted in an unprecedented global loss of 8.8 per cent of working hours, equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs, in 2020 (ILO, 2021). While some workers joined the ranks of the unemployed and are still seeking work, many more have left the labour force altogether. Women, youth and workers in low-skilled jobs, often in the informal economy, have been hit harder than other groups. The longer the distress in labour markets persists, the more the affected workers, their families and their communities run the risk of being trapped in long-lasting poverty. For young people, this crisis will leave scars on their skills, career paths and motivation. It can even result in a lost generation of children and youth, unless swift action is taken to address their needs.While COVID-19 has “turned the world of work upside down”, the crisis hit already weak and fragile labour markets. The deep employment crisis that started a long time ago has damaged the social and economic fabric and, without decisive action, may weaken support for a renewed social contract.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the measures needed to contain its spread have had a devastating impact on the world of work. According to ILO’s latest estimates, the crisis resulted in an unprecedented global loss of 8.8 per cent of working hours, equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs, in 2020 (ILO, 2021). While some workers joined the ranks of the unemployed and are still seeking work, many more have left the labour force altogether. Women, youth and workers in low-skilled jobs, often in the informal economy, have been hit harder than other groups. The longer the distress in labour markets persists, the more the affected workers, their families and their communities run the risk of being trapped in long-lasting poverty. For young people, this crisis will leave scars on their skills, career paths and motivation. It can even result in a lost generation of children and youth, unless swift action is taken to address their needs.While COVID-19 has “turned the world of work upside down”, the crisis hit already weak and fragile labour markets. The deep employment crisis that started a long time ago has damaged the social and economic fabric and, without decisive action, may weaken support for a renewed social contract.

The deep employment crisis driving insecurity

Persistent joblessness and employment insecurity

There has been little progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal of promoting full employment and decent work for all. In the decades before the COVID-19 crisis hit, employment growth was insufficient to absorb the growing labour force: the global number of jobless persons increased from 161 million in 2000 to 188 million in 2019. Unemployment trends do not fully reflect decent work deficits, however, since not all jobs provide income security or good working conditions. In fact, one in five of all employed workers worldwide, including 66 per cent of workers in low-income countries, lived in extreme or moderate poverty in 2019 (ILO, 2020).

In countries lacking comprehensive social protection systems, most workers cannot afford to stay unemployed. In developing countries, an estimated 70 per cent of workers struggle to earn income through informal employment, where salaries are lower than in formal employment, social protection is largely absent and working conditions are poorer. Women, youth, persons with disabilities and indigenous peoples are overrepresented among workers in the informal economy. Their earnings have been hardest hit by the pandemic and the lockdown measures put in place to address it. For most, informal work is not a choice but reflects limited availability of formal, more desirable jobs.

Growing employment instability and the rise of poorly paid, precarious work had been root causes of rising economic insecurity well before the crisis hit. Overall, full-time jobs under open-ended contracts and involving a direct relationship between employer and employee are increasingly rare. Involuntary temporary, part-time and casual work, including zero-hours contracts, subcontracted labour and self-employment are on the rise.

There are new forms of employment and work emerging, partly due to digitalization and automation trends. Workers under many of these new forms of employment – such as own-account workers in a growing “gig” economy – work for more than one company. They enjoy little employment security and limited access to social protection, much like workers under more traditional categories of temporary or other non-standard forms of contract as well as those in the informal economy. While these new forms of work can expand choice in terms of where and when people work, they also shift risks and responsibilities away from employers and onto workers.

This greater labour market flexibility has increased inequalities in wages and working conditions, given that some jobs remain protected while others have been made highly flexible. Workers on non-standard contracts, among whom young people, women, migrants and other disadvantaged groups are overrepresented, earn less than workers on standard contracts, on average, and bear the brunt of employment losses during recessions. A similar segmentation exists where workers in the formal sector benefitting from some degree of social protection coexist with the large informal economy. In addition, worker mobility between the formal and the informal sectors is very limited (Gatti and others, 2014). In contrast to previous crises, the COVID-19 downturn has had a disproportionate impact on women’s work due to its effect on services sectors that are female-dominated. In addition, the increased burden of unpaid work brought by the crisis affects women more than men.

Insecure working conditions

The COVID-19 crisis has shown that systems which leave the most vulnerable unprotected are not only against internationally- agreed norms and standards but are also dangerous. Lacking access to social protection, millions of people have become economically insecure or have fallen into poverty as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Even in countries with comprehensive social protection systems in place, many programmes have not kept up with changes in the world of work. Some schemes, including employer-provided health and pension insurance, depend on contracts with specific employers and many social insurance programmes, from health to unemployment, are tied to salaried employment. Even in-work benefits that are not tied to salaried employment exclude many workers under non-standard contracts.

In addition to providing income security, decent work should not harm or undermine the dignity of workers. Yet, even before the pandemic, close to three million people died every year as a result of work-related diseases and occupational accidents and over 300 million suffered non-fatal health outcomes (Takala, 2019). The pandemic has threatened workers’ health and lives, but it has also heightened awareness of the importance of protecting all workers, especially those providing essential services, who have been disproportionately exposed and infected by the virus. Women, in particular, account for a large proportion of workers in front-line occupations, especially in the health and social care sectors. Health care workers all over the world are working for extended hours in strained facilities as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. The physical and emotional burden essential workers have shouldered during the crisis is resulting in high rates of burnout with serious consequences for mental and physical health. One in four health care workers are currently experiencing depression and anxiety. At the same time, the pandemic has led to a reduction in the availability of mental health services in most countries (WHO, 2020).

The social dialogue at risk

Beyond providing a certain measure of income security and being safe, decent employment is an important source of social identity, particularly when the workplace allows workers to create ties and build networks. Many workers under temporary contracts or those who are outside of an employment relationship altogether may develop little identity through their jobs. Given their vulnerable situation, such workers also face challenges in mobilizing and organizing collectively.

While unions have played a critical role in giving workers a voice and a collective identity, vulnerability has risen with declines in union membership. In most developed countries, where unionization rates are higher, unions have been losing members for the past 30 years. From 2000 to 2018, alone, they lost 24 million members (Visser, 2019). Union density also declined in Asia and Africa, where overall membership rates remain very low, even in the formal sector. In the absence of formal channels to voice their grievances, workers have increasingly resorted to protests, including during the COVID-19 crisis. Unions organized around the traditional employeremployee relationship are not well-suited to give voice to those who do not work for a wage, or who do so outside the formal sector or under non-standard contracts.

The growing incidence of informal and non-standard forms of employment has created momentum for innovative organizations, such as associations of self-employed workers and cooperatives – two different types of representative, membership-based organizations. While some of these new organizations have improved the terms on which workers in vulnerable employment engage in the labour market and have strengthened their capacity to take collective action, many lack the legal capacity to negotiate working conditions. Some unions have also tried to assist workers by mounting legal challenges against worker misclassification (not recognizing workers as employees), and for independent contractors to legally engage in collective bargaining.

Overall, economic growth and, more broadly, development have failed to reduce decent work deficits. Even before the COVID-19 crisis hit, many individuals and families could not rely on stable decent jobs as means to cope with risks or secure livelihoods. The massive employment impacts of the COVID-19 crisis raise fears of social instability and put the social contract under threat.

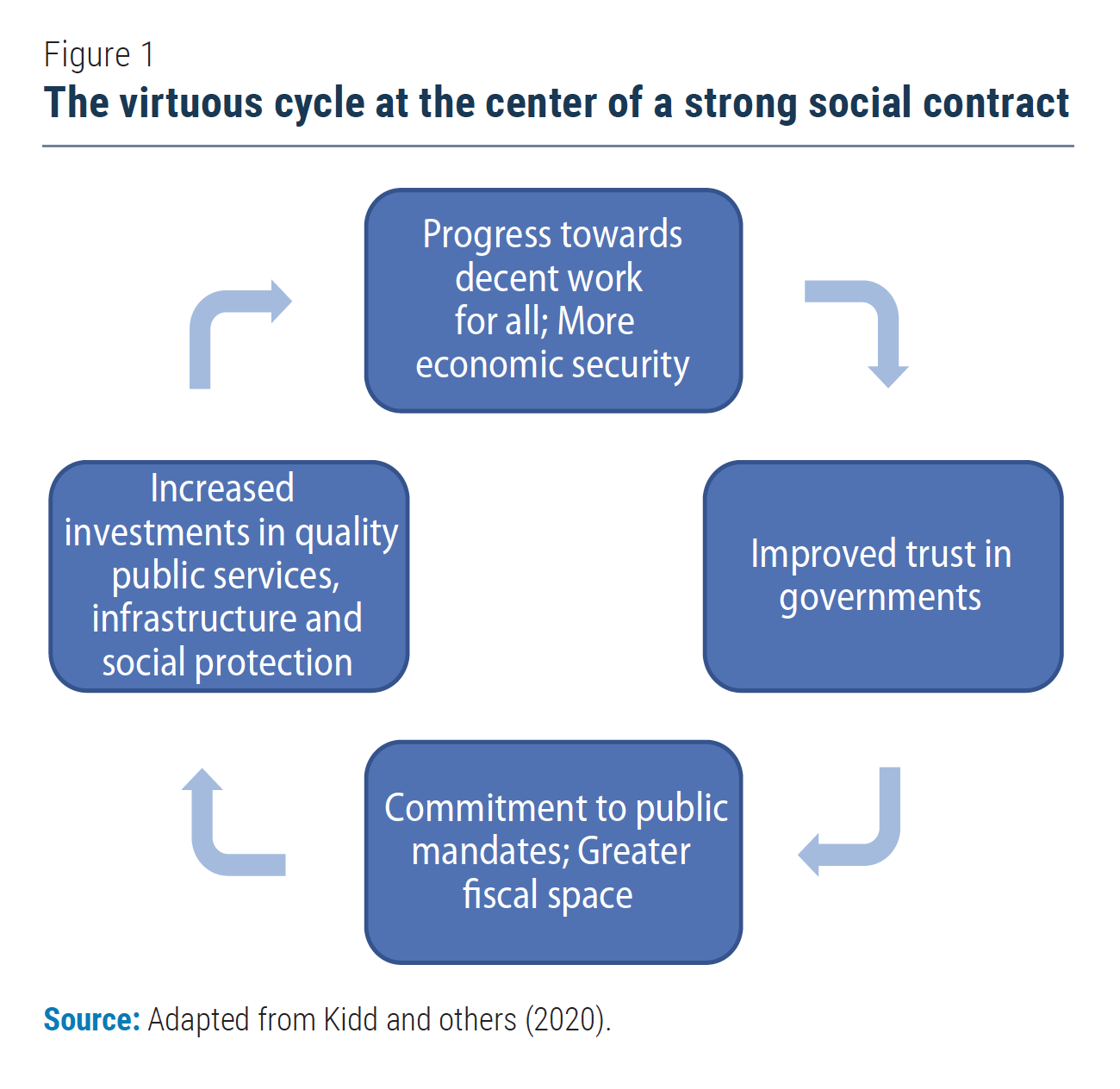

Implications for the social contract

Employment insecurity and the socio-economic uncertainty it generates undermine the relationship between workers, employers and Governments, with consequences for people’s trust in public institutions. Indeed, trust in Governments remains low in many developing countries and has declined in many developed countries over the last decade as a result of deficits in decent work, economic insecurity and widespread dissatisfaction with the quality of public services (Algan and others, 2017; Murtin and others, 2018). Low trust, in turn, leads to a general disengagement with public mandates, foregone tax revenues and therefore less fiscal space to make those public investments that would build trust and ultimately help achieve the SDGs – investments to improve the quality and reach of public services, renew infrastructure, expand social protection and implement far-reaching employment policies. It also affects compliance with laws and public recommendations and therefore challenges the capacity of Governments to address the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises.

Building back better in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis requires breaking the vicious cycle of insecurity, low trust and shrinking policy space. In this context, the UN Secretary-General has called for a new social contract that “integrates employment, sustainable development and social protection, based on equal rights and opportunities for all”. The call for a new social contract recognizes that there is a large gap between changes in the world of work and the policies and institutions meant to manage them. Many of the institutions designed during the Twentieth Century have weakened or else become obsolete.

At the same time, work remains central to people’s lives, societies and politics. If performed in decent conditions, it is not only a means of survival or a way out of poverty, but it gives people purpose and promotes their inclusion. It allows for personal connections; it generates collaborative and associative connections; it defines people’s place in society and promotes greater trust. It is at the heart of a virtuous cycle that strengthens the social contract (see figure 1). These instrumental and social roles of work are relevant across societies now and there is no reason why they should fade in the future. The ongoing transformations must therefore be shaped so that work can continue to fulfill these roles.

At the same time, work remains central to people’s lives, societies and politics. If performed in decent conditions, it is not only a means of survival or a way out of poverty, but it gives people purpose and promotes their inclusion. It allows for personal connections; it generates collaborative and associative connections; it defines people’s place in society and promotes greater trust. It is at the heart of a virtuous cycle that strengthens the social contract (see figure 1). These instrumental and social roles of work are relevant across societies now and there is no reason why they should fade in the future. The ongoing transformations must therefore be shaped so that work can continue to fulfill these roles.

The decisions taken to kick-start the crisis recovery will have dramatic long-term implications for the world of work. Historically, some major crises have indeed reshaped policies and societies in ways that helped protect and advance the interests of workers, thereby reducing inequality and insecurity. These major shocks often tested institutions, practices and reinforced demands for social protection and higher wages. The United States, for instance, put its social protection system in place in the aftermath of the Great Depression of 1929; it also established minimum wages and, through the National Labor Relations Act, empowered the creation of trade unions. Similarly, the United Kingdom established its universal health care system after the Second World War.

While these historical examples are inspirational, it is important to acknowledge that the industrial-era working class that lobbied for strong welfare states in now developed countries no longer exists. In making the case for a renewed social contract, international organizations and other stakeholders must recognize that the structural changes observed in the world of work have diminished the collective voice of workers and weakened their shared identity.

Breaking the current impasse of insecurity and low trust calls for revitalizing collective representation among workers and employers and strengthening the social dialogue, with particular attention to the needs of workers in informal employment and those under non-standard contracts. The role of Governments is particularly important in creating an enabling environment for these vulnerable workers to organize and voice their concerns, encouraging cooperation between social partners. A renegotiation of the social contract requires the active engagement of Governments, employers and workers.

Overcoming the vicious cycle of low trust and disengagement also requires strengthening income security for everyone. In addition to protecting the incomes of workers affected by the crisis, doing so involves expanding and adapting social protection systems to today’s world of work. Access to benefits such as health insurance, paid sick and parental leave, pensions and unemployment benefits need to reach beyond formal employment and be accessible to women and men in all spheres of work, including unpaid work. Interest in a universal, unconditional cash transfer (or Universal Basic Income) has been growing globally in the context of rising economic insecurity and changes in the world of work. While UBIs are costly and involve trade-offs, they also avoid the shortfalls of overly bureaucratic social protection systems. In considering this option, it must however be clear that a regular, basic income does not fulfill the social or purposive roles of a decent job.

Ensuring a more inclusive future of work also requires tackling informality. Beyond expanding the co- verage and outreach of social protection and promoting 5 See United Nations (2020), box 6.1. the representation of workers in informal employment, there is a need to provide incentives to ensure that core labour rights, including rights to occupational safety and health at work, are respected. There should also be space to lower the costs of establishing and operating businesses, reduce regulatory barriers and simplify admini- strative hurdles.

Where workers enjoy job and income security, both companies and workers invest more in training and skill formation. Thus, improving labour standards and providing income security can have a positive effect on productivity and help reduce poverty. In order to make a difference, however, policies aimed at upgrading their skills and enhancing their employability must be complemented by broader demand-side policies that promote decent work opportunities in order to make progress towards SDG 8. Unfortunately, few countries have succeeded in transforming economies to promote decent work. In fact, macroeconomic policies focused narrowly on keeping inflation low and controlling fiscal deficits have often hurt economic growth and increased volatility in the real economy and in the labour market. Emphasis on balancing public budgets has resulted in declines in social spending and in public investments in infrastructure that pave the way for job creation, particularly in times of crisis. Ideally, the current crisis will bring recognition of the fact that creating decent and productive jobs for all in a green and inclusive economy is not only necessary to build back better and deliver on the SDGs, but crucial for people to regain trust in institutions and to restore the social fabric.

Global integration and competition among countries have reduced the national policy space to regulate labour conditions, however. The actions needed to manage changes in the world of work under a new social contract can only be implemented effectively with international cooperation. Solidarity and cooperation are even more pressing in the context of the deep COVID-19 employment crisis. A global deal based on promoting decent work and economic security will build the type of trust needed to foster inclusive and effective multilateralism.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations