Emergence of new forms of work

Emergence of new forms of work

‘Standard employment’—understood as regular, full-time, and subject to labour law—remains the prevailing form of employment in high-income countries, however, new forms of employment have been rapidly gaining ground since the early 2000s. While new forms of work enabled by digital technologies have rapidly been expanding in more advanced economies, they are also spreading to emerging economies, where the effects on the labour markets are likely to be different. For instance, studies show that platform work, one of the new forms of work, has the potential to increase employment opportunities, promote formalization, and reduce gender gaps in emerging economies. Despite the lack of harmonized concepts and definitions, digitally enabled new forms of work are flourishing and the number of people engaged in them is increasing rapidly.

Advanced economies are at the forefront of this wave. A mapping by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions identified nine new forms of employment—namely, ICT-based mobile work, platform work, collaborative employment, casual work, job sharing, interim management, employee-sharing, portfolio work, and voucher-based work—and documented their increasing prevalence in European labour markets.

Digital technologies are creating new jobs and income generating opportunities, including among social groups usually disadvantaged in the labour market such as youth, women, older persons, persons with disabilities, as well as people living in remote areas. While some new forms of employment offer many workers a low-barrier entry into employment, the opportunity for skills development, and the possibility to better balance work and family life, other workers find themselves in an unwanted precarious situation due to the unpredictability of their working hours and income. Such precarious forms of employment are characterized by alternative working patterns, temporary forms of contractual relationships, alternative places of work, and irregular working hours.

Many of these workers are individual contractors, self-employed or freelancers without employee benefits who work in an un-regulated environment regarding working hours, occupational health and safety, and other conditions of work. In particular, digital tools risk creating a permanently on-call culture, where workers are expected to be reachable anytime and anywhere, including outside working hours. This demand for constant connectivity risks blurring of private and professional lives and negatively affecting workers’ health. While some countries, such as France, have adopted labour law on the right to disconnect, the vast majority have not.

Many of these workers are individual contractors, self-employed or freelancers without employee benefits who work in an un-regulated environment regarding working hours, occupational health and safety, and other conditions of work. In particular, digital tools risk creating a permanently on-call culture, where workers are expected to be reachable anytime and anywhere, including outside working hours. This demand for constant connectivity risks blurring of private and professional lives and negatively affecting workers’ health. While some countries, such as France, have adopted labour law on the right to disconnect, the vast majority have not.

A key challenge is that current regulatory frameworks, tax systems, and social protection systems are not adequately equipped to accommodate the new and increasingly diverse forms of employment to protect the benefits and well-being of workers.

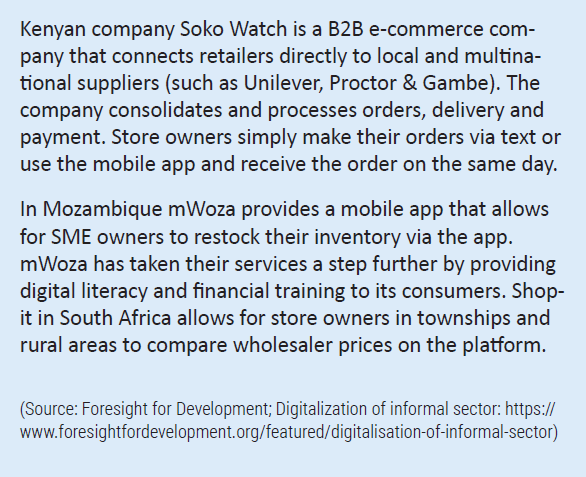

Precarious and informal work—temporary, involuntary part-time, self-employment or insecure forms of work with no or limited access to social protection—are not new. Globally, more than 2 billion people are working informally (equivalent to 62 per cent of the global workforce), mostly in emerging and developing countries, according to the ILO. While digitally enabled new forms of work create new employment opportunities for informal workers in developing countries (see box), they can also exacerbate existing inequalities and discrimination against them, as these platforms seek workers with certain skills (digital skills, basic literacy, etc.). In OECD countries, one third of the labour force are in non-standard forms of employment. Many workers in new forms of work (notably, platform workers) share with informal workers and other workers in non-standard employment the common disadvantage of falling outside the coverage of social protection and labour laws.

Platform work as an example of digitally enabled new forms of work

‘Platform work’—which involves the matching of supply and demand for paid labour through an online web-based platform or applications—is one of the most prevalent and rapidly increasing new forms of digitally enabled work. It also provides an archetypical example of the benefits and challenges that these new forms of employment bring. By some estimates, the use of remote gig economy platforms is growing globally by more than 25 per cent per year. According to the ILO, the number of digital labour platforms increased from 142 to 777 between 2010 and 2020. A few global firms in the United States of America and China account for 90 per cent of the market capitalization value of the world’s 70 largest digital platforms. The share of Europe is 4 per cent and the share of Africa and Latin America together is 1 per cent.

ILO surveys in Europe and North America between 2015 and 2019 suggest that the proportion of the adult population that has performed platform work ranges between 0.3 and 22 per cent. The majority of them are estimated to be below 35 years old and highly educated, in particular in developing countries. Women represent only four in ten workers on online web-based platforms and one in ten workers on location-based platforms. In some countries, app-based delivery platforms are an important source of work opportunities for migrants.

A very small portion of platform workers are directly employed by employers (often to build/maintain digital platforms) and some are in a “grey zone” – difficult to distinguish between an employee or an employer. A vast majority of platform workers are categorized as self-employed or independent contractors whose work is mediated through either an online web-based platform (e.g., translation, legal, financial and patent services, design and software development on freelance and contest-based platforms, gamers, YouTubers or influencers), or location-based platforms (such as taxi, delivery, and home services).

Platform work offers promising opportunities for workers, businesses, and society. For workers, it can offer income-generating opportunities, a vehicle for fostering entrepreneurship and regularizing undeclared work, and the opportunity of low-barrier entry to employment, especially for the young or low-skilled. For businesses, cost reduction and flexibility are the main attractions. At a societal level, it has the potential to be an engine of innovation and employment growth and a chance to improve the provision of services in the public interest.

Yet for all these merits, platform work tends to be a more precarious form of employment due to the unpredictability of work and income, lack of or inadequate social protection (including health insurance, unemployment and disability insurance, or contributory old-age pension) and labour standards, and the shifting of business risks from employers to workers. Developed countries are generally better prepared to respond to the challenges associated with the growing role of digital platforms than countries that have limited resources and weak regulatory and institutional capacities. Still challenges abound.

Working conditions on digital labour platforms are largely regulated by terms of service agreements, which are contracts of adhesion and are unilaterally determined by the platforms (e.g. working time, pay, applicable law and data ownership). They tend to characterize the relationship between the platform and platform workers not as employment. As a result, platform workers cannot access many of the workplace protections and entitlements that apply to employees. Awareness among platform workers is also low of any formal process for filing a complaint or seeking help, where they exist. Moreover, platform workers are often unable to engage in collective bargaining, mainly because they are geographically dispersed. Most workers on digital labour platforms do not have social security coverage. Encouragingly, regulatory authorities in many countries have started to address some of the issues related to working conditions on digital labour platforms.

COVID-19 has highlighted policy gaps and challenges

Since early 2020, measures put in place by governments to contain the COVID-19 pandemic have further accelerated the pace of digital transformation, expanded e-commerce (which has grown two to five times faster than before the pandemic) and virtual transactions (online banking, telemedicine, telehealth), and considerably increased the number of people working remotely. Some forms of platform work (e.g. delivery, on-line surveys and freelance) expanded during the pandemic, while others (e.g. ride hailing and home services) experienced a decline. As workers and employers have gained in experience and confidence in remote working during the crisis, it is predicted to remain as an alternative form of work as the world returns to a “new normal”—a hybrid working environment. The increased prevalence of remote working will provide an opportunity for companies to redesign work processes, as some work, especially those involving routine tasks, can be automated or performed remotely. As a result, while some workers (those with specialized skills, creative professionals) may seek to become freelance or self-employed—enabled by web-based platforms – for additional income, more flexibility and better work and family life balance. Conversely, others – displaced by technological advances – may need to find jobs in different sectors. According to McKinsey Global Institute, up to 25 per cent more workers than previously estimated may need to switch occupations.

The COVID-19 crisis further highlighted platform workers’ vulnerabilities. For example, competition created by an over-supply of platform workers triggered a downward pressure on prices/earnings. Similarly, the pandemic highlighted the lack of paid sick leave coverage faced by platform workers – especially among those working in the transport sector (ride-hailing and delivery) – who kept working at the expense of their own safety and health.

At present, the landscape of platform workers’ access to social protection is a complex one made up of a patchwork of piecemeal policies put in place by national governments. The growth of new forms of employment, exemplified by the growth of platform work, poses the risk of deeper division within labour markets between well-protected workers in standard forms of employment and those with limited access to social protection and rights at work. It also draws attention to regulatory gaps. Many platform workers are demanding to be recognized as employees, not as independent contractors in charge of their own social insurance and with control over their income, as platforms claim. The proliferation of court cases is a symptom of the regulatory gaps that enable platforms, rather than labour law, to establish the status and rights of workers.

Policy actions to protect non-standard workers, including workers in digitally enabled new forms of work, are not yet sufficient

Social policy is an important instrument to address the challenges posed by the rise of non-standard employment, including digitally enabled new forms of work. Countries have been implementing policy measures to improve protection of non-standard workers. For example, several OECD countries, such as France and Germany, plan to introduce “individual activity accounts” of benefits that are not only portable from one job to another but can also be used flexibly by workers according to their needs.

Many countries are taking steps to expand existing social protection coverage to non-standard workers. For example, France requires platforms to cover the accident insurance costs of self-employed workers. Many Latin American countries extend social security for self-employed workers.

Indonesia and Malaysia offer work injury and death benefits to workers on some labour platforms. A district court in China ruled that a platform company should pay injury benefit to a delivery worker on its platform. In response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, Ireland has extended sickness benefits to all workers. Finland and the United States provided unemployment benefits to uninsured self-employed workers. These measures to improve social protection coverage are all welcome developments, but they have been mostly piecemeal and those included in COVID-19 response/stimulus packages will be withdrawn unless they become regular features of national social protection systems. Solutions are also needed for practical challenges such as clarifying who pays the employer contribution for workers in new forms of work, especially platform workers; and where platforms are required to provide sick leave, how to ensure a platform worker’s access to sick leave without the risk of losing the job, or be less competitive on the platform.

Leaving no one behind – adapting labour regulations and social protection systems to digitally-enabled new forms of work

Employment is becoming more diverse. Policymakers should seek to strike a balance between flexibility and incentives for innovation and entrepreneurship, and workers’ protection and income security. This requires a shift away from one-size-fits-all solutions to more tailored policies that consider the unique opportunities and challenges of different types of new forms of work. In the absence of labour market regulatory frameworks to address the special conditions of digitally enabled new forms of work, the rise of non-standard employment, a phenomenon rooted in labour market deregulation, is being exacerbated by digital transformation. Better data, policy experimentation, and more evidence-based policy analysis are required to help existing labour regulations and social protection systems to adapt and accommodate changes in the world of work.

A fundamental issue arising from the changing world of work in the digital age is to safeguard workers’ protection and income security. Among the panoply of measures available to governments, investment in lifelong learning to assist workers to take advantage of new job opportunities should be a priority. There is also room to implement practical and incremental measures to improve income security and the protection of workers, building on initiatives already being explored, including COVID-19 responses.

Increasing regulatory agility to respond to new forms of work: New types of jobs and new ways of organizing work have led to labour market practices and relationships that defy the traditional concepts underpinning labour market regulations and institutions. For example, from the perspective of the employers of platform workers or users of their services, it is not clear if platform workers are employees or not. It is also not clear if an individual contractor using a digital platform to mediate between clients and providers of services is an employee or employer. Such ambiguity has been frequently exploited by digital labour platforms and employers to avoid paying employer contribution to social protection schemes, leaving workers uncovered. Often, workplace safety and other working condition regulations are similarly absent for new forms of work. As the pace of digital transformation accelerates, the need for regulatory and administrative reform become more urgent in order to increase the agility of labour regulations to respond to the new reality in the world of work and to make social protection universal. For example, regulation to clarify the criteria by which a platform worker should be considered an employee could be a step in the right direction; encouragement and facilitation to increase representation of workers in new forms of employment in social dialogue are also good starting points to support necessary regulatory reforms.

Making permanent COVID-19 emergency response measures to promote universal social protection: Digital transformation creates new types of jobs and work arrangements that are further increasing the ranks of non-standard workers who are not (or only partially) covered by national social protection systems. Furthermore, digital transformation is making obsolete certain jobs/tasks while increasing the productivity of others. To eradicate poverty in all its dimensions and to leave no one behind in the digital age, universal social protection, including nationally determined floors, is an imperative. The emergency measures put in place in response to the socioeconomic impact of COVID-19, extending income support to informal and non-standard workers, demonstrated the power of social protection to keep people out of poverty and deliver the 2030 Agenda’s promise of “leaving no one behind”. Governments should invest financial resources to make some of these measures permanent to increase social protection coverage towards the target of universal social protection.

Portability of benefits—tying social protection to individuals rather than jobs: An emerging trend in the future of work is the growing number of jobs that will allow for flexibility in terms of how they are performed, by whom, where, and when. Workers are also welcoming the flexibility to control their own work lives. Existing evidence from surveys and interviews with 12,000 workers in 100 countries, and with 70 businesses, 16 platform companies and 14 platform worker associations operating in multiple sectors and countries indicates that workers in the digital age may work for multiple clients/employers and change jobs frequently facilitated by digital platforms. Traditionally, social insurance schemes have been employment-based, tying benefits to jobs. Such systems no longer suit the new reality of the world of work. To leave no worker unprotected, social protection benefits should be tied to the worker instead of the job. The adaptation needed in social protection systems will be to increase the portability of individual’s benefits across jobs, even across national boundaries.

Flexibility in the schedule of contribution: A distinctive feature of the future world of work in the digital age is the flexibility of the labour market that makes new types of work and work arrangements possible. While this flexibility can support a better work-life balance, sometimes it also implies irregularity of work and income, even for high-skilled workers. Taking a lesson learned from expanding social protection coverage in rural areas, flexibility in contribution schedules should be increased to accommodate irregular income streams of workers of the digital economy, especially platform workers and individual contractors.

Authors: Isabelle Deganis, Makiko Tagashira, Wenyan Yang, Division for Inclusive Social Development.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations