Ongoing and emerging global trends, such as globalization, new technologies, the rise in global inequality, demographic shifts, climate change and threats generated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, will dramatically impact societies and individuals of all ages, and will determine the nature and future of work.

Ongoing and emerging global trends, such as globalization, new technologies, the rise in global inequality, demographic shifts, climate change and threats generated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, will dramatically impact societies and individuals of all ages, and will determine the nature and future of work.

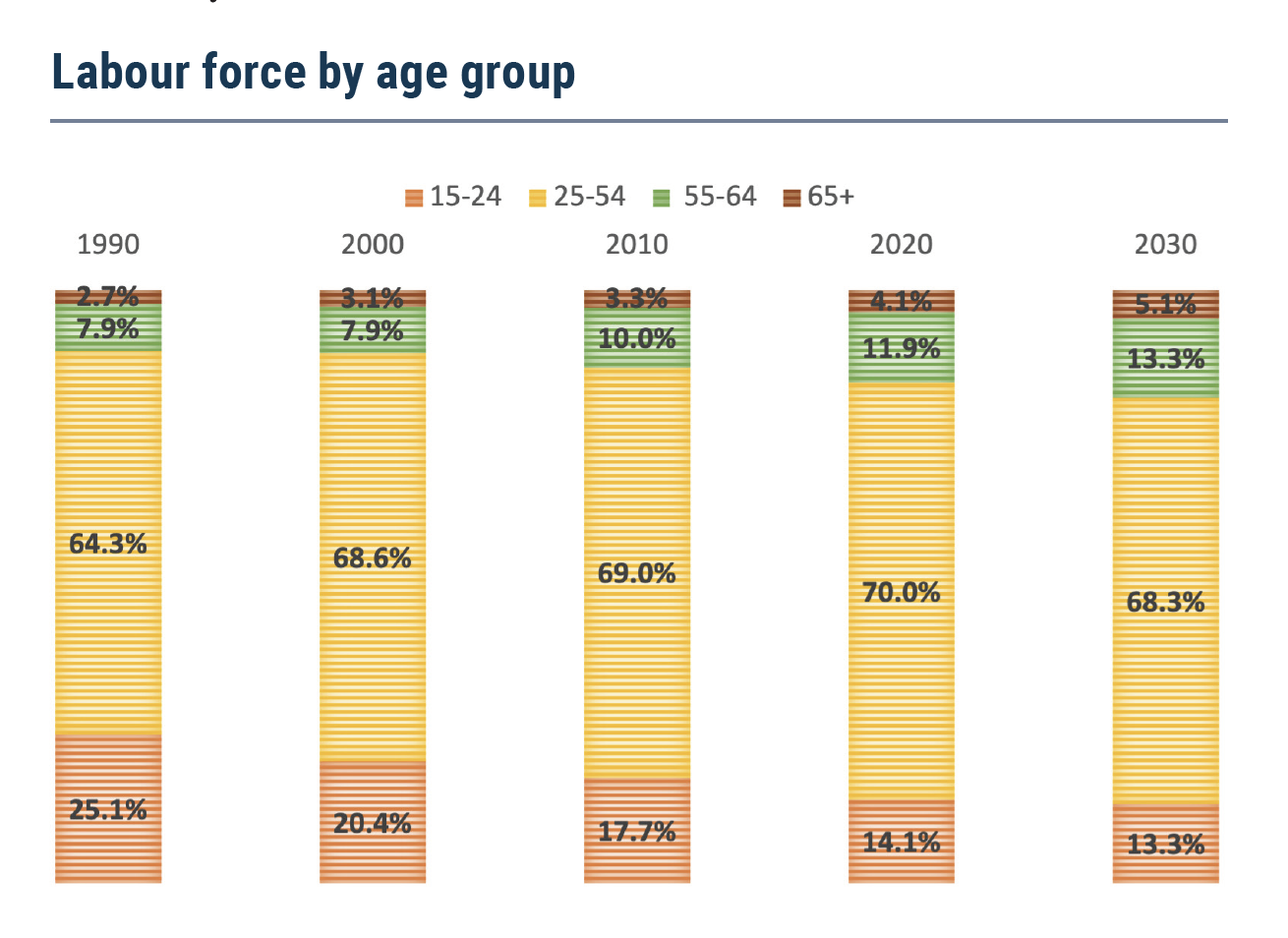

At a time of persistent inequalities, an inclusive future of work is fundamental for sustainable development, ending poverty and leaving no one behind. Population ageing influences economic growth and labour force participation, and the share of persons aged 65 years and over in the labour force at the global level is estimated to continue the current upward trend in the coming decades (see figure 1). Global life expectancy at birth has increased by 7.7 years between the periods 1990–1995 and 2015–2020, and is projected to increase by an additional 4.5 years between the periods 2015–2020 and 2045–2050. Survival beyond the age of 65 is also improving in most parts of the world, and projections show that such an increase will affect all countries within the next three decades.

Population ageing is often depicted as a challenge to economic progress and to the sustainability of public budgets, yet available research and data suggest that its economic consequences are not pre-determined, and that when appropriate policies are put in place, population ageing can in fact benefit economic development and economic progress while, at the same time, promoting age-inclusive societies.

For instance, research shows that across countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, giving older workers greater opportunities to work would raise GDP per capita by as much as 19 per cent over the next three decades. Indeed, in 2018 people aged 50 years and over contributed $8.3 trillion in economic activity to the economy of the United States of America, an amount equivalent to 40 per cent of the country’s GDP.

Companies benefit from age-diverse teams. Preliminary findings of a joint initiative of AARP, OECD and the World Economic Forum to identify and share multigenerational and inclusive workforce practices suggest that employers with age inclusive workforces are more resilient and better positioned to be more successful in a competitive environment.

According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, entrepreneurs aged between 50 and 80 years old make up a sizeable portion of all entrepreneurs, and tend to start businesses at a rate that is comparable to or higher than younger entrepreneurs (aged between 18 and 29 years old). Older entrepreneurs (aged between 65 and 80 years old) are slightly more likely to employ five or more people, whereas younger entrepreneurs are, on average, slightly more likely to be running non-employer businesses.

Governments can harness population ageing for economic progress and ensure economic security in old age by:

Rethinking old age and population ageing and embracing diversity in old age

Assumptions and stereotypes regarding old age need to be challenged. Central to this is the acknowledgement that diversity is a defining characteristic of old age, and the consequent reflection of this heterogeneity in public policies, including in employment and labour market policies.

Heterogeneity among older persons is observed in needs, capacities, preferences and health and economic status, among other factors, suggesting that a successful response to population ageing aimed at benefiting from the longevity revolution needs to be multifaceted. The recognition of the intersecting forms of discrimination experienced by persons at all stages of their lives, including gender and disability, is essential to understand what old age looks like.

Heterogeneity among older persons is observed in needs, capacities, preferences and health and economic status, among other factors, suggesting that a successful response to population ageing aimed at benefiting from the longevity revolution needs to be multifaceted. The recognition of the intersecting forms of discrimination experienced by persons at all stages of their lives, including gender and disability, is essential to understand what old age looks like.

In the field of work, acknowledging diversity in old age entails putting in place systems that support older persons who are unable or choose not to work, while enabling others who can and wish to work to continue doing so. In such systems, older persons are able to navigate future transitions with freedom from fear and insecurity.

Identifying and removing barriers to access decent work

Older persons may choose or be forced to work beyond retirement age for different reasons. Whatever the circumstance, in order for older persons to remain economically active, policies must remove barriers to their participation in the labour market while protecting their right to freely choose whether to work and providing opportunities to extend employability. Barriers to the full participation of older persons in employment are multiple and intersecting, and reflect attitudes, legislation and the institutions of work. They include:

‣ Age-based discrimination. One of the main barriers faced by older persons in employment, age-based discrimination manifests itself in the form of ageist individual, institutional, systemic or structural practices. The coexistence of variables, such as gender and disability, exacerbates age-based discrimination at work. Measures that address age discrimination, including policies, legislation and public awareness campaigns, are crucial to remove barriers for older workers in recruitment, promotion, training and employment retention, as is supporting older entrepreneurs. As an employer, the public sector should model age-inclusive employment. Stronger diversity legislation and the extension of disability rights can also protect against discrimination based on an intersection of grounds, such as age, disability and sex, in the employment of older workers.

‣ Rigid labour markets. Offering flexible and part-time work arrangements, which are highly valued by older workers, as well as exploiting the potential of new digital technologies, including robotics and artificial intelligence to support employment among older persons can incentivize older workers to extend their working lives. While information and communications technologies (ICT) have become ubiquitous in the economic and social life of both developed and developing countries, digital divides continue to prevent ICT from achieving their full development potential, particularly in the least developed countries. New areas of employment that arise from the digital transition might provide new opportunities for older employees.

‣ Inadequate access to lifelong learning systems. Lifelong learning applies a holistic approach to education and training, by providing access to formal and informal learning to everyone at all phases of life, from early childhood education through to adult learning. Inadequate access to training opportunities for older persons can hamper their ability to continue working or find new employment, as many skills become obsolete in the rapidly changing labour market and the demand for skilling, reskilling and upskilling grows.

‣ Informal employment and unpaid care work. The participation of older persons in insecure and low-productivity work or informal employment is also a barrier to their access to decent work. Unpaid care work, often performed by women, can also be a barrier to the participation of older workers in the formal labour market.

Improving access to social protection

The great diversity that characterizes old age means that while many older persons will be able and willing to continue working beyond retirement ages, for many this will not be an option. Well-funded universal social protection systems are critical to guarantee that older persons, in particular the most disadvantaged, have access to at least an adequate minimum income in the form of contributory or non-contributory pensions and key services such as health care and long-term care. Strong and responsive social protection systems based on the principles of solidarity and risksharing are decisive for the future of work and are a foundation for social inclusion and economic prosperity. Further, where such systems adopt a life-course approach that provides protection from all transitions across the lifetime, including childhood, disability, maternity, unemployment and old age, people are more likely to reach old age in better economic, health and social conditions.

Download the UN DESA Policy Brief #112: Harnessing longevity in the future of work

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations