Introduction

Introduction

Even though rural poverty has declined rapidly in recent decades, poverty remains primarily a rural phenomenon and the poorest in rural areas are at risk of being left behind. The World Social Report 2021 (United Nations, 2021) finds that successes in poverty reduction have not always led to lower rural inequalities or to a closing of the rural-urban divide. Indeed, disparities in access to basic services and opportunities continue to exist within rural areas and between rural and urban areas, and can be persistently high for specific population groups, such as indigenous peoples and women. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the precarious situation of the rural poor and disadvantaged groups, by reducing incomes, limiting mobility and threatening livelihoods and food security.

Countries that have succeeded in reducing rural poverty and inequalities have relied on a range of policies including, among others, investments in infrastructure and public services, and the promotion of inclusive agricultural growth and access to land. A key policy area to reduce both rural poverty and inequalities is social protection. There is ample evidence of the positive impact of social protection on poverty and inequality reduction as well as on its ability to promote inclusion (United Nations, 2018). Access to regular and adequate social protection benefits prevents poverty and reduces vulnerability through the lifecycle. It reduces the need to rely on negative coping strategies- such as pulling children out of school or selling assets — when households face economic shocks. In the long term, social protection can help smooth consumption, build human capital and enable investments that improve rural people’s resilience to future crises.

Faced with disproportionate levels of poverty and exclusion, and considering the high levels of seasonal and informal employment in rural areas, often under unsafe working conditions, access to social protection is essential for those living in rural areas. Yet social protection coverage in rural areas is generally lower than in urban areas. Globally, 56 per cent of the population in rural areas lack health coverage, for instance, compared to 22 per cent in urban areas (ILO, 2017). This brief discusses the challenges to accessing social protection for rural populations and offers policy recommendations on how to overcome them.

Availability is key

To expand access to social protection in rural areas, a crucial point is to ensure that a social protection floor is in place to begin with. The most recent data from 2015 shows that only 29 per cent of the global working-age population has access to comprehensive social protection systems (ibid). Such a floor should include both social assistance and social insurance programmes. Social assistance schemes are commonly tax-financed and help establish basic guarantees for all. They ensure a basic level of income security and access to essential health care. Social pensions and child benefits with universal coverage in rural areas, for example, would go a long way to alleviating the worst forms of extreme poverty and deprivation. Social insurance schemes, on the other hand, provide basic protection to individuals in the case of income loss and are typically financed through contributions from workers and/or their employers. Social insurance programmes can also contribute to the broader decent work agenda by encouraging formalization of employment — particularly relevant in rural areas given the high levels of informality. Ensuring the availability of both social assistance and social insurance schemes that take into account the idiosyncratic risks and challenges most relevant to rural areas is vital to protect rural populations throughout the life course.

Challenges to rural access

There are a number of financial, administrative and programme design barriers that hinder people’s ability to access social protection in rural areas, even when schemes are available. Few social protection programmes are tailored to rural populations or the specific vulnerabilities and constraints they face, particularly in developing countries. Beyond ensuring programme availability, understanding these barriers is vital to achieve increased social protection coverage in rural areas.

Financially, a lack of stable and sufficient incomes among rural populations hinders participation in social insurance schemes. Agricultural income is highly seasonal and weather-dependent, especially in low-income countries. This makes regular contribution to social insurance a challenge. Seasonal workers, for example, may earn their primary incomes in a short period of time during the year. As a result, making regular monthly contributions will be more difficult during, and particularly at the end of, the off-season. Rather than investing their limited financial resources on pension or other schemes, many people living in poverty in rural areas must prioritize more immediate needs. For social assistance, the costs associated with traveling to banks or other sites to collect benefits, being away from work or complying with programme conditions may reduce the potential benefit of the programme to participants. Given the higher levels of poverty in rural areas, this may represent a hidden cost that many cannot bear.

Administrative hurdles can further undermine the reach of social protection programmes in rural areas. On the supply side, the administrative capacity required to identify and register beneficiaries, monitor payments and contributions and control for potential errors are less readily available in rural than in urban areas. Remoteness further increases the cost of delivering social protection. Moreover, reserving time to register and queue for benefits can result in significant losses of income, particularly for workers in casual employment who have to miss work or for those who have to close a small business; especially when it takes a substantial amount of time to reach the nearest rural service point.

Pervasive informality in rural employment further complicates access to social protection. Workers in rural areas are twice as likely to be in informal employment (80 per cent) than workers in urban areas (44 per cent) (ILO, 2018). Workers in informal employment are insufficiently covered by social protection or not covered at all. In fact, lack of social protection coverage is often used to identify informal employment. Similarly, seasonal and casual work also rarely provide access to social protection. Additionally, rural residents can be excluded from social protection due to a lack of coverage of their specific economic sector. Programme design in some countries leaves workers in different agricultural subsectors — such as livestock, fisheries or forestry — either out of scope or even explicitly excludes them. Informality is thus both a consequence and driver of the lack of social protection coverage.

Even among types of employment and economic sectors that are not explicitly left outside the scope of social protection programmes, there can be eligibility thresholds related to working hours, duration of contracts and enterprise size that disproportionately affect rural workers, even those in formal employment. In addition to eligibility criteria, the frequency and timing of payments and slow accrual of rights further discourage rural workers in non-standard forms of employment from signing up to social insurance schemes. For social assistance programmes, a further complication is the fact that few are anchored within a legal framework – meaning benefits can be cut at any time due to a lack of funding and beneficiaries cannot claim any legal rights (ILO and FAO, 2021).

Improving rural access to social protection

Overcoming the structural barriers to accessing social protection faced by rural populations is an imperative for the achievement of the SDGs without leaving rural people behind. This calls for addressing them head-on.

Regarding financial barriers, in addition to ensuring the availability of tax-financed, social assistance programmes, Governments can consider modifying contribution schemes to account for employment types common in rural settings and offering more flexible payment options to account for seasonality and fluctuating earnings. Seasonal rather than monthly contributions could be made in line with the harvest season when income is highest to increase participation in social insurance, for example. Reducing or temporarily suspending contributions in the aftermath of a shock could further increase accessibility. Participation in social insurance schemes can also be improved by offering subsidies to those living in poverty. Finally, the hidden costs of participation to accessing social protection programmes in general can be lowered by simplifying administrative procedures, ensuring programme conditions are not overly onerous and making services readily accessible.

There have been innovative solutions targeted at improving access to social protection in remote and lowdensity rural areas. In rural Mongolia, for instance, social protection take-up improved when one-stop shops were introduced in 2007, gathering services of multiple government ministries in single locations, minimizing multiple trips for remote and time-constrained agricultural workers (ILO, 2015). These combined-service centres have since been set up in all provinces and most districts, with mobile vans bringing access to those living in the most remote areas.

Governments are also increasingly utilizing digital technologies in improving the reach of social protection services among rural residents. Delivering benefits and collecting contributions on mobile banking applications, for example, offers real solutions that reduce transaction and travel costs for those that live in remote areas. However, efforts to close the digital divide in rural areas will have to be stepped up in order to ensure these services will be available to all. To promote connectivity in rural areas, Governments can ease regulatory requirements for alternative business models such as community networks, create a more enabling environment for investment in underserved areas through incentives such as tax breaks and create a universal service fund to expand rural access financed through some form of mandatory contribution from telecommunications service providers (ITU, 2020). It must also be kept in mind that utilization of digital technology should not become a new barrier to service access by those without devices or digital skills. Deployment of technological innovation should be complemented by measures to close the digital divide, including training in digital literacy.

Agricultural micro-insurance is another developing field. For lower-income farmers, it can reduce risk at a lower cost than traditional insurance. Agriculture is still a vital part of the livelihoods of rural populations and it is particularly vulnerable to large covariate shocks such as droughts or floods, which are increasingly exacerbated by climate change and are a major cause of income loss. This is particularly relevant for smallholder farmers, who often lack irrigation and depend on unpredictable rainfall, and find it difficult to cope with crop losses. The Kilimo Salama micro-insurance initiative in Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania, for instance, is a weather-indexed insurance that pays claims based on weather measurements. Compared to traditional insurance, Kilimo Salama is simpler and less costly (both to operate and to purchase), while its mobile phone-based administration and payment system has allowed it to reach smallholders in remote areas with poor access to financial services (Sibiko, Veettil and Qaim, 2018). However, micro-insurance programmes are complementary measures and should not be a substitute for universal social insurance programmes.

Existing social protection frameworks can also be extended to reach groups that are currently excluded from social protection, such as informal workers. Governments can take advantage of and expand on the existing social protection infrastructure, including those temporary measures implemented in response to COVID-19. An existing payment delivery mechanism can be used, for example, to deliver a specific benefit to a larger group of people. Extending existing frameworks avoids fragmentation of the broader social protection system and could make it easier for rural residents to switch between agriculture and other sectors of the economy without losing access to benefits.

New schemes can also be adopted to meet specific needs of rural populations. This option allows policymakers to implement particular design elements that are attuned to rural specificities. Such an approach helps minimize the chance of people falling through the cracks of the system but does imply a greater degree of policy fragmentation.

New schemes can also be adopted to meet specific needs of rural populations. This option allows policymakers to implement particular design elements that are attuned to rural specificities. Such an approach helps minimize the chance of people falling through the cracks of the system but does imply a greater degree of policy fragmentation.

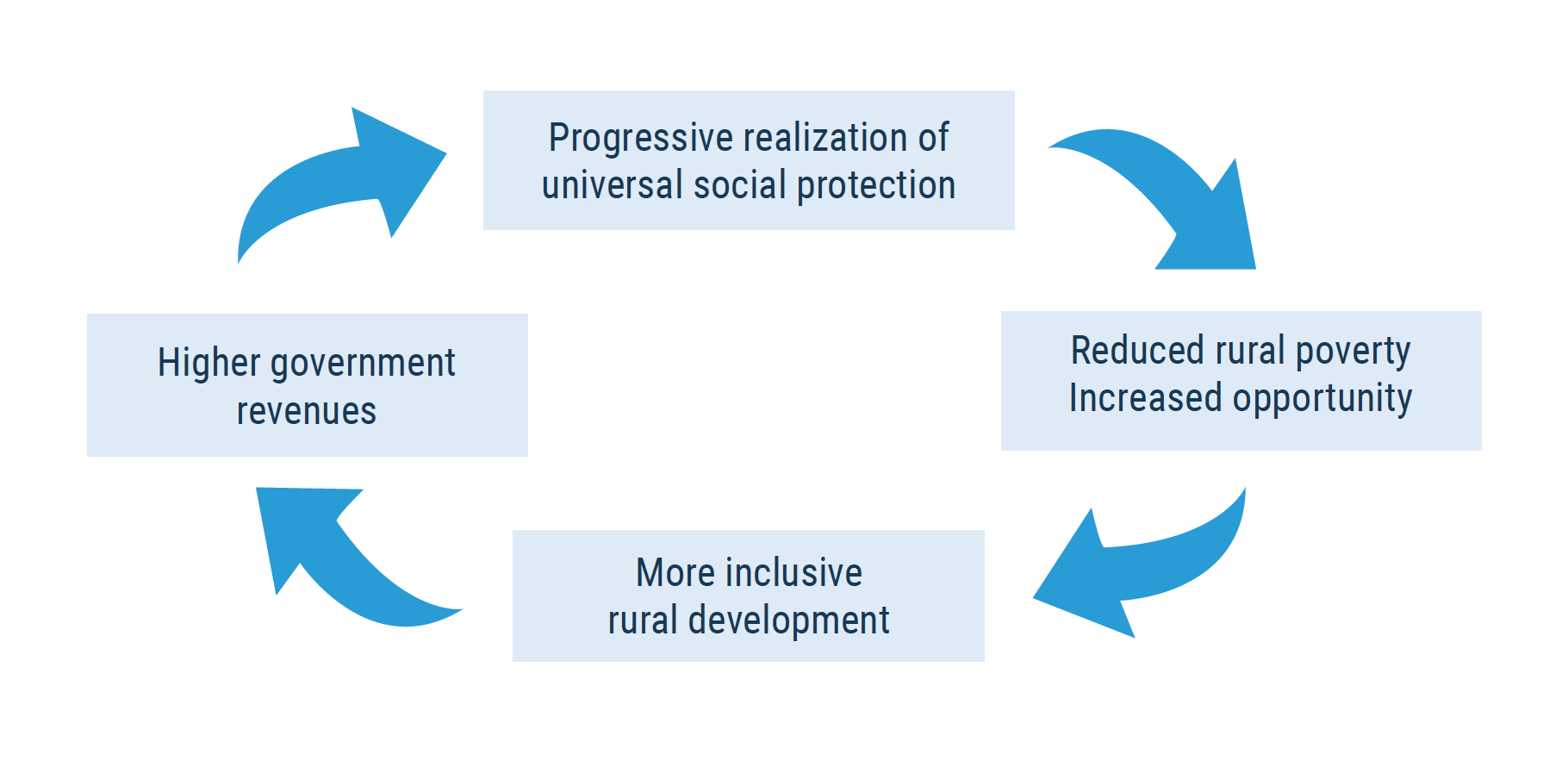

Additionally, social protection schemes should be anchored within strong legal and institutional frameworks to ensure stability and long-term funding. The lack of legal provisions often leaves beneficiaries unable to claim their rights. Lack of legal grounding is especially prevalent for social assistance schemes, which are often small-scale and temporary. Furthermore, programme design principles — such as eligibility criteria, the timing and level of benefits, institutional responsibilities and funding — should all be clearly specified in order to establish inclusive, accountable and predictable schemes. Ultimately, well-designed and inclusive social protection systems can bring direct benefits to rural populations. Provided the services offered are of good quality, they will highlight the role of Government and engender trust — reinforcing the social contract. A positive cycle can be created where social protection contributes to lower levels of rural poverty, increases opportunities and fosters rural development. This will in turn deliver more tax revenue to the State; allowing for improved service delivery. This virtuous cycle can be a sustainable way to extend or implement social protection measures, including floors, for all in rural areas and ensure income security throughout the life course, in line with SDG 1.3.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations